Jan 16, 2025

Whitepaper

How bad is it?

Plastic debris has become one of the most stubborn pollutants in our ocean, lurking in every corner of marine ecosystems. It’s everywhere, from the deepest parts of the ocean to the most remote islands. This pollution doesn’t just harm the environment; it has severe economic impacts too. The problem has gained significant attention in recent years, with the United Nations, the G7, G20, and various other organizations launching initiatives to combat it.

Nearly half a billion tonnes of plastic is now produced annually, and it's projected to increase as populations rise and economic growth continues. Most of this waste comes from plastics with lifetimes of under five years, such as packaging, consumer goods and textiles, and the sad reality is, although the majority is sent to landfill or incineration, only 9% is successfully recycled, leaving 22% that is mismanaged. This leads to millions of tonnes of fresh plastic waste finding its way into aquatic environments yearly, with 1.5 to 11 million tonnes entering our ocean.

Every. Single. Year.

If we keep this up, by 2050, plastic in the ocean will outweigh fish, and by 2060, we’ll be generating over one billion tonnes of plastic waste annually, more than tripling the build-up of plastic in aquatic environments, exacerbating the environmental and health implications.

How does plastic end up in the ocean?

As plastic production has ramped up over the last 70 years, so has the subsequent pollution, which finds its way into the ocean via a number of routes, with the primary one being our rivers. Of course, rivers aren't the only route. Equipment from the shipping and fishing industries, typically designed to withstand harsh ocean conditions, makes up a significant portion of pollution out at sea, and beach littering or direct disposal at sea are relatively minor contributors. As it stands, there's 30 million tonnes of plastic waste floating in the ocean, and another 110 million tonnes stuck in our rivers, which will remain there or be washed out to sea.

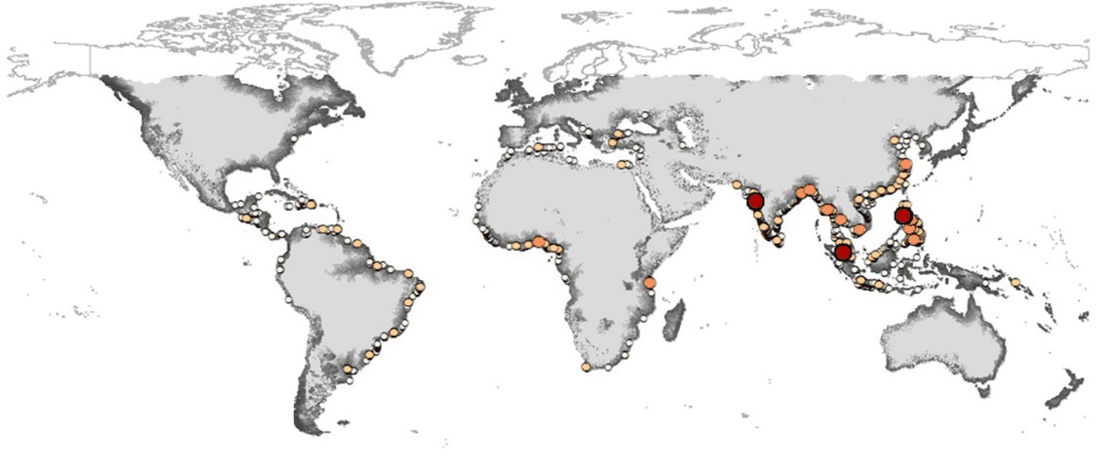

Even if we managed to reduce mismanaged plastic waste, these rivers would continue to leak plastic into the oceans for decades. Research has shown that less than 2,000 rivers account for 80% of plastic flowing into the ocean, with middle income countries being the biggest polluters. This pollution can be heightened by seasonality too, with floods dramatically increasing plastic mobilization. In some places such as Bangladesh, this can be as much as 41 times more compared to non-flood conditions.

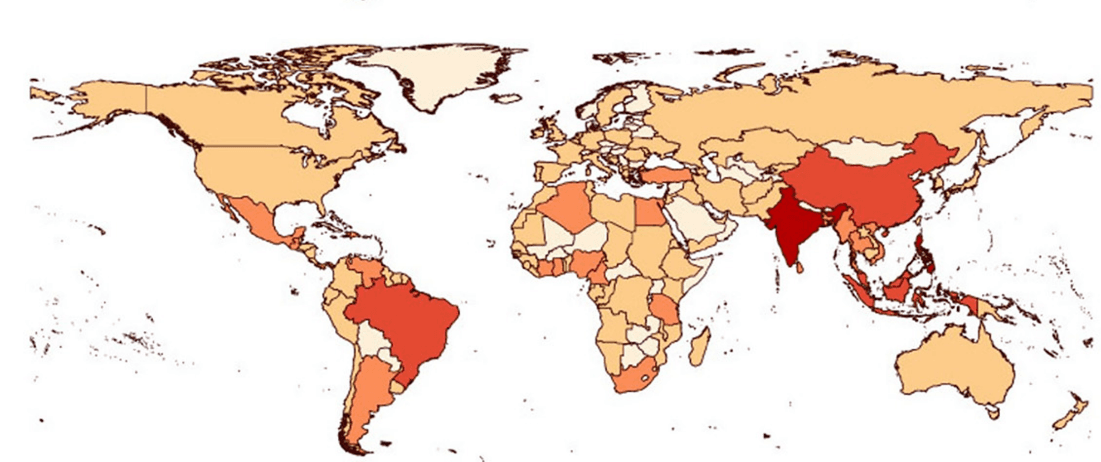

Figures below. Global emissions of plastic into the ocean

(A) A heat map showing the total emitted plastic into the ocean per country

(B) The distribution of plastic entering the ocean through rivers. The circles represent the 1656 rivers accountable for 80% of the total plastic waste entering the ocean, with the larger and darker circles signifying the most polluting rivers

Where does it all go?

So, what happens to all this plastic once it makes its way into the ocean? Roughly half is denser than sea water and immediately sinks from the surface, remaining in locations where fragmentation occurs. Over 80% of the floating half ends up washed up on a coastline within a month of arriving into the ocean, presenting significant issues for the coastal environment. The remaining portion of the floating plastic can end up circulating coastal regions or being washed out to sea, aided by wind and ocean currents. The fate of each item is determined by its physical properties and the environment that it's in. Material density, trapped air and natural processes such as surface biofilm growth impact buoyancy and can cause an object to either float or descend into deeper waters.

Ocean Gyres

Plastic that manages to drift further out into the ocean can accumulate in the oceanic gyres, large systems of circulating ocean currents. The most infamous of these is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). It’s a massive floating island of trash in the Pacific Ocean, roughly twice the size of New South Wales (Australia), or three times the size of France. It contains 100 thousand tonnes of ocean plastic, 80% of which has come from the fishing industry, with some of it dating back to the 1960s. You'd have thought that the accumulation of pollution would make removal efforts easier, but the average density is roughly the weight of a football per football field area, and despite 75% of the total weight being made up of plastic items larger than 5cm, there are approximately 1 trillion pieces of microplastic dispersed across the GPGP. It's therefore very difficult to efficiently collect the plastic waste, which continues to breakdown into the ocean.

The implications

Plastic pollution’s reach extends far beyond what the eye can see, causing significant harm to marine wildlife, ecosystems, human health, and the global economy.

Threats to marine wildlife

Our oceans' inhabitants, from the tiniest microorganisms to the largest marine mammals, are suffering due to plastic pollution. The very durability that makes plastic so useful also makes it a persistent problem in our oceans. Once plastic enters the ocean, it can remain for decades, causing continuous harm. Animals often mistake plastic for food or become entangled in it. This issue affects nearly 1000 species, including endangered ones. Whales have been spotted in the GPGP, indicating their exposure to the vast amount of pollution. Since the patch contains nearly 200 times more plastic than biomass, you can expect that plastic may often be mistaken for food by marine life.

Impact on oxygen and carbon cycles

The presence of plastic in the ocean also affects vital biological processes. Phytoplankton, such as Prochlorococcus, which produce a significant portion of the world’s oxygen, are negatively impacted by the toxins released from plastic. This disruption affects their ability to produce oxygen and reproduce. Furthermore, the ocean's role in carbon sequestration is compromised. Zooplankton that ingest microplastics consume 40% less carbon biomass, reducing the efficiency of the carbon pump, which helps transfer carbon from the surface to the deep ocean. This reduced efficiency can have broader implications for global carbon cycles.

Human Health Risks

Microplastics have made their way into our food, water, and even the air we breathe. Studies show that microplastics can pass through the blood-brain barrier in animals within hours, and their long-term effects on human health are still being studied. Potential health risks include acute and chronic toxicity, carcinogenicity, and developmental issues.

Economic Burden

The economic cost of plastic pollution is immense. A Deloitte study estimates that plastic pollution costs the global economy up to $19 billion USD annually. This includes the impact on fisheries, tourism, aquaculture, and the expenses related to cleaning up plastic waste. Additionally, derelict fishing gear can cause significant damage to vessels, posing serious risks to maritime operations.